Tenants of 89a: Full Story

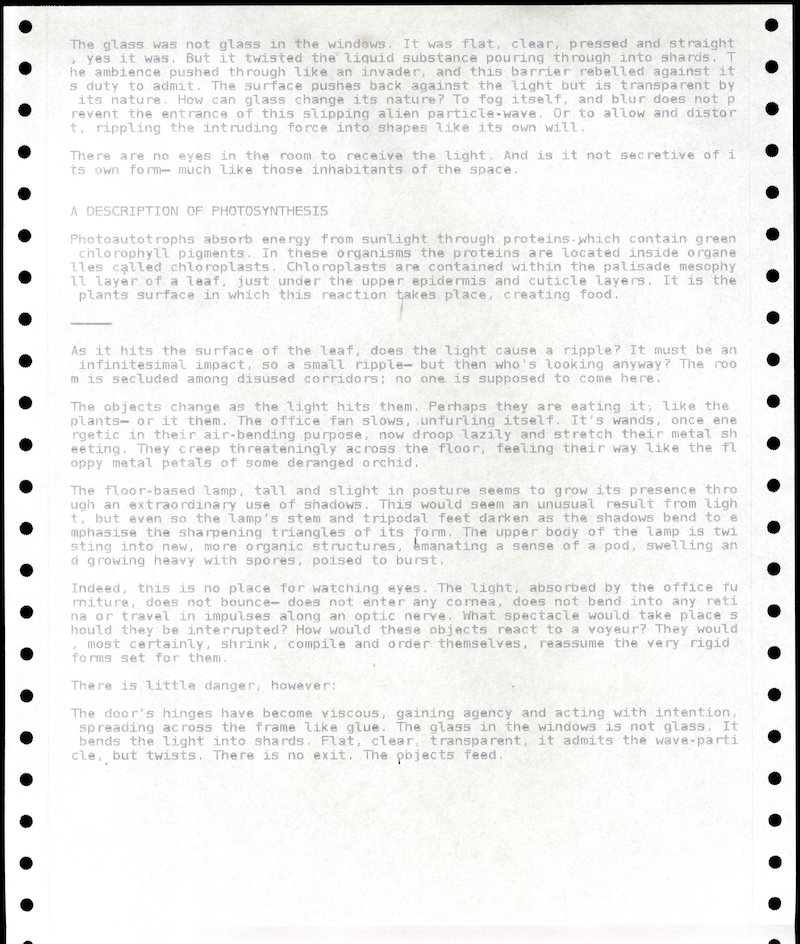

The glass was not glass in the windows. It was flat, clear, pressed and straight, yes it was. But it twisted the liquid substance pouring through into shards. The ambience pushed through like an invader, and this barrier rebelled against its duty to admit. The surface pushes back against the light but is transparent by its nature. How can glass change its nature? To fog itself, and blur does not prevent the entrance of this slipping alien particle-wave. Or to allow and distort, rippling the intruding force into shapes like its own will.

There are no eyes in the room to receive the light. And is it not secretive of its own form— much like those inhabitants of the space.

A DESCRIPTION OF PHOTOSYNTHESIS

Photoautotrophs absorb energy from sunlight through proteins which contain green chlorophyll pigments. In these organisms the proteins are located inside organelles called chloroplasts. Chloroplasts are contained within the palisade mesophyll layer of a leaf, just under the upper epi- dermis and cuticle layers. It is the plants surface in which this reaction takes place, creating food.

—————

As it hits the surface of the leaf, does the light cause a ripple? It must be an infinitesimal impact, so a small ripple— but then who's looking anyway? The room is secluded among disused corri- dors; no one is supposed to come here.

The objects change as the light hits them. Perhaps they are eating it, like the plants— or it them. The office fan slows, unfurling itself. It’s wands, once energetic in their air-bending purpose, now droop lazily and stretch their metal sheeting. They creep threateningly across the floor, feeling their way like the floppy metal petals of some deranged orchid.

The floor-based lamp, tall and slight in posture seems to grow its presence through an ex- traordinary use of shadows. This would seem an unusual result from light, but even so the lamp’s stem and tripodal feet darken as the shadows bend to emphasise the sharpening triangles of its form. The upper body of the lamp is twisting into new, more organic structures, emanating a sense of a pod, swelling and growing heavy with spores, poised to burst.

Indeed, this is no place for watching eyes. The light, absorbed by the office furniture, does not bounce— does not enter any cornea, does not bend into any retina or travel in impulses along an optic nerve. What spectacle would take place should they be interrupted? How would these ob- jects react to a voyeur? They would, most certainly, shrink, compile and order themselves, reas- sume the very rigid forms set for them.

There is little danger, however:

The door’s hinges have become viscous, gaining agency and acting with intention, spreading across the frame like glue. The glass in the windows is not glass. It bends the light into shards. Flat, clear, transparent, it admits the wave-particle, but twists. There is no exit. The objects feed.

There is a visitor in the corridor. They cannot hear the signal of her sharp stiletto clacking steadily towards their room. They do not have ears. As far as is known, the objects have no mechanism for detection, nor necessarily any will to act on such an incident. But we also know that observa- tion does strange things to the behaviour of objects. There is something alarming in both her ap- pearance and her decisive trajectory along the corridor.

Her confident posture is noted as giving a sense of purpose and belonging. Whether this is mis- placed is yet to be determined. They are unaware both of her posture and her implied entitlement. It might be said at this point that she is unwelcome.

There is a sheet of paper clasped in her hand, freshly printed. She scans it occasionally. It is a set of directions, a map, in the form of a story. She is the writer.

She glances curiously through the doorways at the nondescript rooms; her hand alights on a han- dle and turns, pushes, despite it odd stickiness, and steps briskly through. She notes the odd transition that takes places upon leaving the liminal void of an office corridor and entering the end-space of a destination, a place with purpose and work to be done.

Like a door, a window can be a two way portal, but of an unusual kind. No visible matter passes through. Photons can transition the transparent barrier, and so can sight. The voyeur can equally become the victim of a reversed gaze.

The surprise displayed on her features upon entering shows that the room is unexpectedly ordi- nary. The relaxed structure of her shoulder blades tightens, and is noted accordingly.

She had not anticipated the impact of introducing a character to the story. She has changed the variables, she realises, and now sees her entrance as a fumblingly pompous and ill-conceived. Her keen eye flicks across the room, suddenly suspicious.

She observes the contents of the room:

Windows, bright and closed, possible reason for the stuffiness of the air; A tall standing lamp and a fan hiding low beside the wall;

A table supports a computer monitor and a printer;

The floor is carpeted.

Her posture is tense now. She glowers at the humming lamp as though it would reveal secrets of its clandestine behaviour under the heavy pressure of her gaze. It only whirrs spiritedly in return. She glares closer. It is quite impertinent, she thinks, in its normalcy. She turns her gaze to the lamp. It does not flinch or flicker. In fact, ever single object conspires to maintain an obstinately nondescript impression. This palpable stubbornness in the face of a witness was possibly the only revealing evidence of irregular tendencies.

She makes her way to the computer and sits, placing the sheet of paper on the table and aligning herself to the angle of the furniture. She opens the web browser and logs into her email.

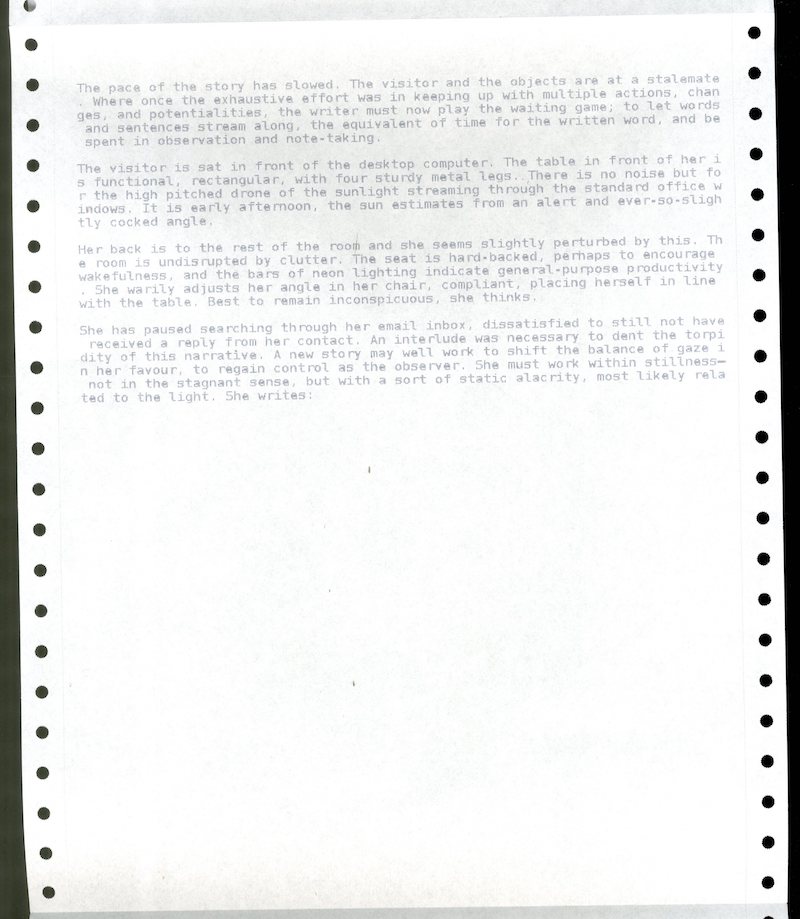

The pace of the story has slowed. The visitor and the objects are at a stalemate. Where once the exhaustive effort was in keeping up with multiple actions, changes, and potentialities, the writer must now play the waiting game; to let words and sentences stream along, the equivalent of time for the written word, and be spent in observation and note-taking.

The visitor is sat in front of the desktop computer. The table in front of her is functional, rec- tangular, with four sturdy metal legs. There is no noise but for the high pitched drone of the sun- light streaming through the standard office windows. It is early afternoon, the sun estimates from an alert and ever-so-slightly cocked angle.

Her back is to the rest of the room and she seems slightly perturbed by this. The room is undis- rupted by clutter. The seat is hard-backed, perhaps to encourage wakefulness, and the bars of neon lighting indicate general-purpose productivity. She warily adjusts her angle in her chair, compliant, placing herself in line with the table. Best to remain inconspicuous, she thinks.

She has paused searching through her email inbox, dissatisfied to still not have received a reply from her contact. An interlude was necessary to dent the torpidity of this narrative. A new story may well work to shift the balance of gaze in her favour, to regain control as the observer. She must work within stillness— not in the stagnant sense, but with a sort of static alacrity, most likely related to the light. She writes:

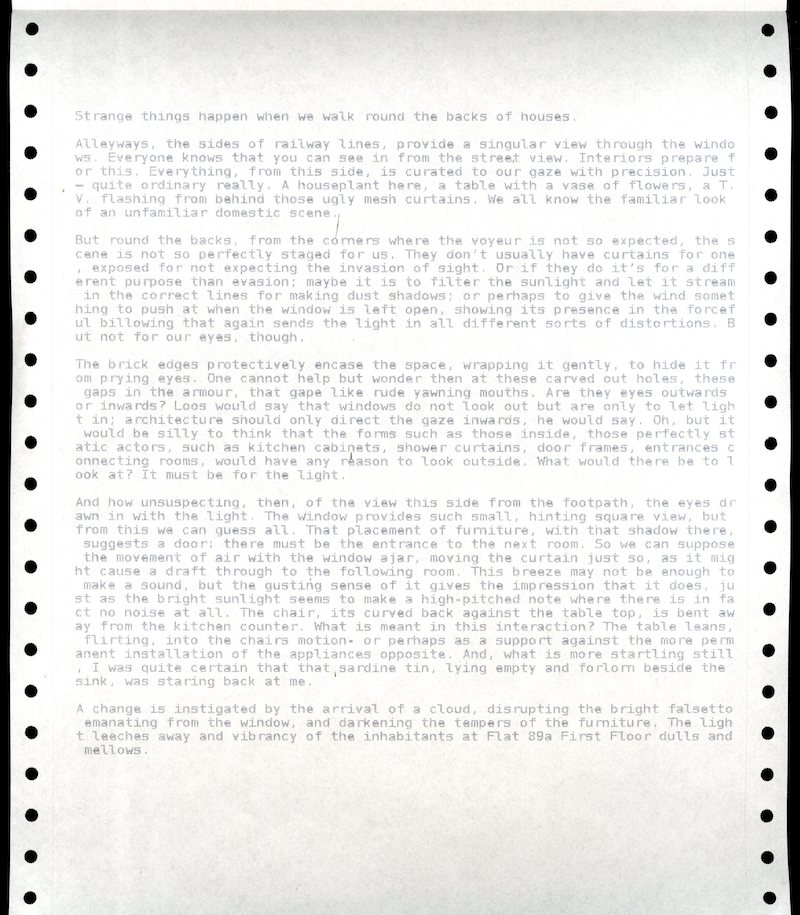

Strange things happen when we walk round the backs of houses. Alleyways, the sides of railway lines, provide a singular view through the windows. Everyone knows that you can see in from the street view. Interiors prepare for this. Everything, from this side, is curated to our gaze with precision. Just— quite ordinary really. A houseplant here, a table with a vase of flowers, a T.V. flashing from behind those ugly mesh curtains. We all know the familiar look of an unfamiliar domestic scene. But round the backs, from the corners where the voyeur is not so expected, the scene is not so perfectly staged for us. They don’t usually have curtains for one, exposed for not expecting the invasion of sight. Or if they do it’s for a different purpose than evasion; maybe it is to filter the sun- light and let it stream in the correct lines for making dust shadows; or perhaps to give the wind something to push at when the window is left open, showing its presence in the forceful billowing that again sends the light in all different sorts of distortions. But not for our eyes, though. The brick edges protectively encase the space, wrapping it gently, to hide it from prying eyes. One cannot help but wonder then at these carved out holes, these gaps in the armour, that gape like rude yawning mouths. Are they eyes outwards or inwards? Loos would say that windows do not look out but are only to let light in; architecture should only direct the gaze inwards, he would say. Oh, but it would be silly to think that the forms such as those inside, those perfectly static actors, such as kitchen cabinets, shower curtains, door frames, entrances connecting rooms, would have any reason to look outside. What would there be to look at? It must be for the light. And how unsuspecting, then, of the view this side from the footpath, the eyes drawn in with the light. The window provides such small, hinting square view, but from this we can guess all. That placement of furniture, with that shadow there, suggests a door: there must be the entrance to the next room. So we can suppose the movement of air with the window ajar, moving the curtain just so, as it might cause a draft through to the following room. This breeze may not be enough to make a sound, but the gusting sense of it gives the impression that it does, just as the bright sun- light seems to make a high-pitched note where there is in fact no noise at all. The chair, its curved back against the table top, is bent away from the kitchen counter. What is meant in this interac- tion? The table leans, flirting, into the chairs motion- or perhaps as a support against the more permanent installation of the appliances opposite. And, what is more startling still, I was quite cer- tain that that sardine tin, lying empty and forlorn beside the sink, was staring back at me. A change is instigated by the arrival of a cloud, disrupting the bright falsetto emanating from the window, and darkening the tempers of the furniture. The light leeches away and vibrancy of the inhabitants at Flat 89a First Floor dulls and mellows.

She is content with what she has written. It was very clear, she thinks, that the objects were re- maining as they ought to be— objects to a subject. On consideration it was, perhaps, a little chaotic in its description, but such is the nature of a domestic subject. The report of the light seems accurate and she is satisfied. She reads it closer. The tone was quite altered from that concerning this room. She had felt constrained to keep the language within strict boundaries. The change of space must be impacting her language. Yes, she thinks, making an effort to colloqui- alise— the rooms rigidity in its current state must be insidiously asserting itself upon her. It seems a narrator is not immune to their subject. She keeps quite still while wondering at her new position in the grand hierarchy of objects and whether entering the scene was unwise. Tentatively she shifts her posture to a sloppy angle, and immediately glances to the fan behind her. It is still buzzing along industriously. Sighing, she relaxes her shoulders somewhat.

The writing had served as a distraction from the conundrum of the room and she was now feeling its absence dearly. She read through her email to her friend, a researcher and physicist working at NASA, Dr J***** T******. It had contained the story and a simple query for his thoughts. Nothing has arrived.

Concentrating this time, she focuses her attention on her peripherals, attempting to discreetly gauge any changes in her fellow inhabitants of the room and wondering if they were aware of her looking. She returned her gaze to the screen, searching for clues perhaps in the still empty inbox.

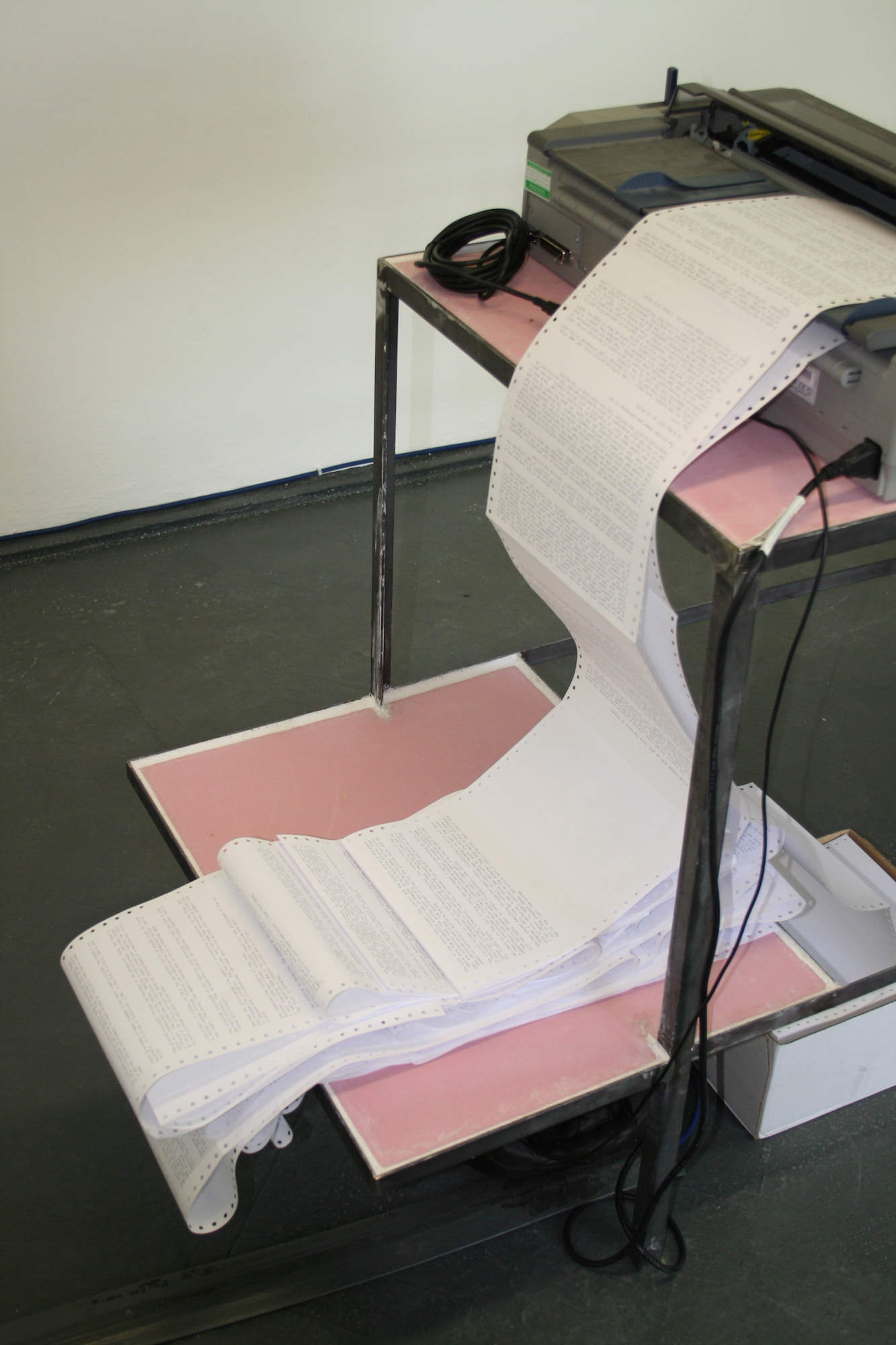

A sharp sound startles her troubled thoughts, quite distinctly different from the high pitched drone that emanated from the windows. This is more aggressive and she locates its source as the print- er. It was the first action to come from one of the objects and she watched each of them now sur- reptitiously, expecting them all to spring into noisy action. Looking back to the printer now, certain that the change was jealously precipitated by her attention to the computer, she notices that a sheet of paper is jerking steadily outward. The noise was purely functional then. How interesting— what was the cause, who gave the order? At this question she looked again at the other objects, accusingly this time. There were no wire no wires on the floor, no bluetooth or wifi devices present... she was reminded of the two-slit experiment in which scientists decided that photons must be communicating with one another from the other side of the barrier.

The printed sheet was addressed to her. On 8 May 2017 at 15:10:09,

Hey *****,

Sorry for the grossly late reply - I was suffering with a virus last week after finally getting back from the US. This is amazing... I was interested in the imparting of momentum from the light to the surface...

Essentially because light can be thought of as a bunch of particles called 'photons', you can say that although they are masses, they have non-zero momentum. This means that when they impart this momentum in the surface they contact. A host of photons will move an object noticeably, and hence we have to nudge our space craft back onto it's orbit every once in a while.

Maybe more interesting to you, remembering your mention of wave-particle duality, there is also the photo-electric effect. From shining a light on a metallic surface, electrons can be liberated de- pending on the energy of the light. It's one of the most famous and solid proofs of the wave-parti- cle duality. Visible light is not always enough to liberate the electrons, depending on the surface being illuminated. It's also important to note that the photoelectric effect is a property of metallic surfaces only...

Best of luck with your experimentation, I hope this helps...

JT

A gap in the cloud cover, which apparently acted as containing shield until now, brings a sudden wave of light in through the glass— portal, is it? It certainly isn’t a barrier. Light is a trigger, it seems. She knew this already. The room brightens, reflecting back off the white painted walls that now seem to glow and hum.

There is equipment on the table. She must begin the assemblage. Feeling energised by the Doc- tor’s analysis, she sorts through the apparatus.

Plugging together a power cable and various boxes with dials on them, the investigator reflects that she has very little idea what she is doing but she makes notes of every detail all the same. It is hard to guess the workings of such items which are so carefully encased in packaging to con- ceal themselves. She wonders at their inner workings and the principles behind them.

Deploying the object is simple enough. She carries it from the desk over to the standing fan, figur- ing that it was best to crack the most troublesome and the others will fall in line. The approach is not easy. The spinning blades of the machine press and fold the air, shoving it towards her with alarming force. The dials upon the machine remain inert.

THE INTRUDER IS REMOVED FROM THE STORY

The gaze involves the acting of one object upon another. The subject is the active party while the object is the passive. So the subjects argue as to the activity of the intruder-object. The activity of this object appears to have been an attempt to act upon them.

Nonsense, creaks the table. It is only a perception of being observed which attributes agency and vibrancy to this moving object.

The fan and lamp enter a serious disagreement. Lively flickering and buzzing dominate the room for a time.

All matter acts upon all other matter, surely it is no stretch to imagine being looked back at.

Yes, imagination... key word there! Projecting a fiction of imagined activity upon an object, its ‘vi- brancy’ is entirely dependent upon your perception of it, hence how could it be called indepen- dent?

The table is keeping minutes, being closely connected to the computer, and groans.

The seminar is adjourned. The light dims in the room as the cloud sweeps back across the sun. The glass in the window is indeed glass.

(2017)